Hutton Lowcross and Guisborough Forest

Forestry England are providing courses with funding from Sports England. I am into the 3rd session of the course on Archaeology focusing on the Guisborough Forest. This blog aims to record some of what I have learnt on the course with additions resulting from my living in the area for over 45 years.

Thanks to Lorna Routledge who is our link into Forestry England for all the organisation Tea, coffee and biscuits; and to

Matt Beresford of MBArchaeology, who is leading the course, for the inspiration.

Guisborough Forest covers an area on the Cleveland escarpment, with a disused railway line to the north, the North York Moors to the south, Roseberry Topping to the West and Hutton Village to the east. The railway line was the Middlesbrough and Guisborough (M&G) railway. The history of the line and the ironstone mines it served is summarised here with more information available in this blog.

Most of the area is known as Hutton Lowcross and incorporates several woods, including High Bousdale Wood, Harrison Close Wood, Thomas’ Wood, Hall Heads Wood, and others. The wooded area, managed by Forestry England, continues East as far as Slapewath and Charltons. It was all planted with pine trees in 1920s as a source of wood. In recent years some of this this has been harvested and deciduous woodland planted or allowed to grow back.

According to Key to English Place-names (nottingham.ac.uk) The area is known as Hutton Lowcross. Is a ‘Hill-spur farm/settlement’, near Lowcross Farm, ‘Logi’s cross’: hōh (Old English) A heel; a sharply projecting piece of ground; cros (Middle English) A cross, the Cross. (Also late Old English); tūn (Old English) An enclosure; a farmstead; a village; an estate.

Pinchinthorpe: ‘Outlying farm/settlement’. The Pinchun family held land here in the 12th and 13th centuries. Originally, ‘east outlying farm/settlement’; þorp (Old Norse) A secondary settlement, a dependent outlying farmstead or hamlet.

Information on the area is available in Wikipedia, Hutton Village – Wikipedia, suggesting the Low cross was reference to someone’s name, as in Logi’s Cross. The area was mentioned in the Domesday Book as ‘Hotun’ or ‘Hotun Loucros’. See also http://visionofbritain.org.uk/place/13058 and the paragraph later on Domesday Book.

Looking at Old Maps on line (oldmapsonline.org) a map of 1607 shows this part of North Yorkshire. The map covers a large area and ‘Gisburgh’ is shown with a sizable river close by? This is obviously no longer evident but the route of the river appears to follow the route of Howle Beck, the stream through Tockets and Skelton Beck, to the north of the town, entering the sea East of Marske, where Saltburn now is. Tributaries are Chapel Beck, which runs through the town, Hutton Beck and Sandswath Beck, which rises near Pinchinthrope. If this was a sizable river then it has diminished in time over the last 400 years. Being a sizable water course suggests it was navigable and hence the importance of Guisborough being located where it is. A number of water mills operated in the area, particularly, as evidence by the 1853 Map, Tockets Mill, which has been restored and is now a tourist attraction, and Howl Beck Mill, both used to mill corn. In Guisborough there exists Mill Street which ends at Chapel Beck by New Road Bridge.

Howle Beck Mill is no longer in existence, although there is a Howle Beck Mill Farm on modern maps. The farm does exist, although not much evidence of the mill is left and the race shown on the 1853 map is no longer shown on modern maps. The only evidence of other mills existing is in the Domesday Book, suggesting there was one at Hutton.

Archeaological Identification

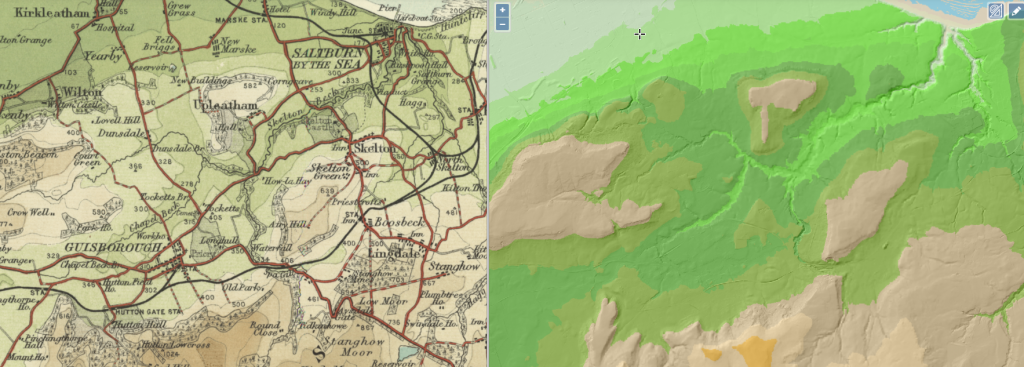

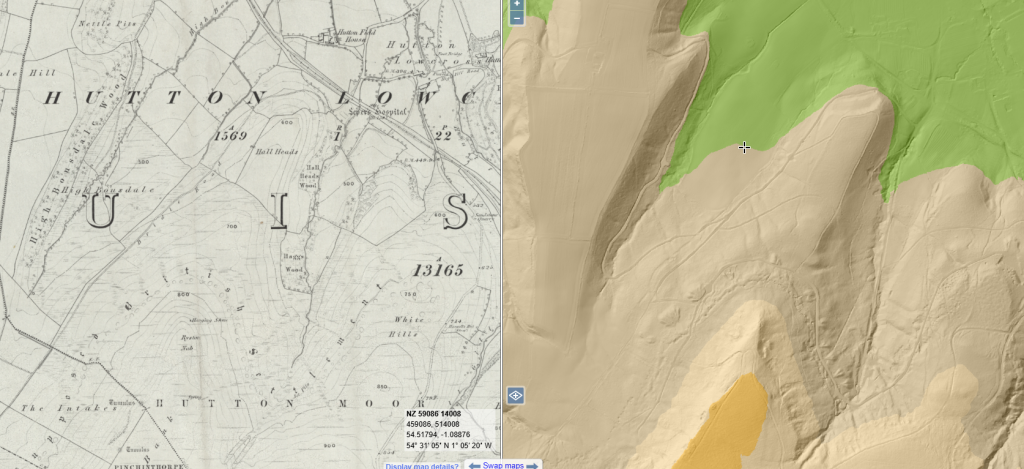

Using the LiDAR maps available through the national library of Scotland, it is evident that there could have been a sizeable water course close to Guisborough.

LiDaR, Light Detection and Ranging, is an airborne mapping technique Information is available here. The technique highlights irregularities in the landscape. Other non-obtrusive techniques include field walking, where artifacts are collected and their exact position is logged, geophysics resistivity and magnetometry, where underlying structures can be identified, and metal detecting, which is only good for finding metal objects. These are unobtrusive techniques towards identifying archaeology, They give an indication of where things are, or might be, but not what they are.

Test Pits

To identify what the archelogy actually is more obtrusive techniques are used which also provide a time line. Test pits are often dug at a spot that some archaeology is suspected, or where it is convenient to do so. A test pit is typically 1m x 1m x 1m deep, but in the first instance the surface material is removed and the the material beneath to a depth of, say, 10 cm is removed, sieved and any artifacts noted and kept for washing and further identification. The pit is dug progressively in 10 cm layers and hence when the artifacts are examined, through knowing the level they came from a time line can be determined. If a structure appears, however, this is left in tact and in place and the digging progresses with it ion place. Hence walls are found. By looking at the wall of a pit different soil strata can be identified, again providing a time line for the history of the pit.

Larger area may be excavated in a similar manner with the soil being scraped away and observed.

Maps

The National Library of Scotland provides maps for most of Scotland England and Wales. Using this resource provides maps for the Hutton Lowcross and Pinchinthorpe area with 5 maps showing the ordnance survey in 1853, 1893, 1913, 1927 and 1950.

The 1853 Map is of interest as this shows the route of the railway lines when ironstone mining started.

Historically the area has been mined for Jet, Alum and Ironstone. Alum, a double salt of Potassium and Aluminium Sulphate, was extracted from the shale beds and used as a mordant in the dyeing industry. This map indicates the escarpment was a ‘Supposed British Settlement’ and indicates Jet workings.

The moorland area to the south has many prehistoric sites. Cairns and Tumuli are marked on the map. More modern maps indicate an ironstone settlement further south along Percy Rigg. As a group we walked up to the Hanging Stone and along Ryston Nab and found the Tumulus marked on the above map. Many of these have been excavated during the 19th century, often by local clergy, in search of prehistoric grave goods. Instead of being mounds, covered in stone, they now tend to be basin shaped where the excavations have taken place.

The 1853 Map also shows that a brick field. existed at the east end of Harrison Close wood, along the disused railway. Bousdale Brickworks is now used as part of an exercise trail. Bousdale House is just to the South. This is a private residence and has the date 1671 above the door.

An Archeological Time Line

The earliest human occupation is believed to be 900000 years ago. Up to 12000 years ago this has been designated the Lower, Middle or Upper Paleolithic period.

The last Ice age was approximately 12000 years ago, i.e circa 10000 BC. not all of the UK was covered in ice. The northers parts were and the southern parts weren’t. At this time the land we call the UK was linked to Europe via Doggerland. This low land has since been claimed by the North sea, but that didn’t happen overnight. As land became uninhabitable, people, who were hunter gatherers of the Stone age, moved south. Doggerland being flooded from about 8000BC, resulted in the last links to Europe being via what is now East Anglia. By circa 4000BC Mesolithic Britain is cut off from Europe.

10000 years ago, about the time of the last ice age the period is known as Mesolithic and may be considered the Middle Stone age. Population continued to be hunter gatherers, following the migrations of wild animals. Being nomadic, they travelled across the then landbridge of Doggerland into what is now Germany, the Netherlamds and Europe.

Tools in the stone age may appear rudimentary but are quite sophisticated. They are generally made of flint and shaped and split to create sharp edges and points. With time the smaller pieces of waste, resulting from making tools, were being used.

From 4000BC settlements started to appear as the nomadic lifestyle diminished, and this was the start of the Neolithic Period. Monuments were also being built as means of worshiping the Gods. Earthwork monuments began to be transformed int wooden and then stone monuments and henges.

The Stone Age transformed to the Bronze age about 2500 BC with the discovery of copper, a malleable material useful for tool making and then the mixture of 90% copper and 10% Tin to form Bronze, equally malleable but stronger and tougher. During the Bronze age communal tombs were replaced by barrows and Henges by stone circles. Also the herding of cattle and pigs starts to be replaced by the farming of sheep.

The Roman empire was expanding and attempts to invade the UK were thwarted by the existing tribes until a successful invasion along the Kent Coast in AD 43. The Romans started to settle and moved North, but found it more difficult as the Northern tribes resisted. Roman settlements weren’t adopted everywhere. Iron Age settlements persisted along side. Romans tended to build with stone and ornate art work. Iron Age buildings tended to be large round houses made of wood, wattle and daub and thatched rooves. The Romans extended there influence to the Midlands by AD 50 and by AD 65 the 9th Legion occupied as far north as York.

By AD 118 Emperor Hadrian had built most of his wall in the north to delineate the extent of his empire. This extended from the Solway Firth across to Wallsend, Newcastle. The Emperor Antonius Pius ordered the construction of the Antonine Wall around AD142. This stretched across the central belt of Scotland.

By AD 400 the Romans in Britain were in decline as their resources were moved elsewhere to defend the empire. There were links between the British tribes and the Saxons, who acted as mercenaries and militia for the British Tribes The Saxons start to take over In Ad 650 when there were 7 Kingdoms. The Heptarchy were the seven petty kingdoms of Anglo-Saxon England that flourished from the Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain in the 5th century until they were consolidated in the 8th century into the four kingdoms of East Anglia, Mercia, Northumbria, and Wessex. Northumbria was split into two, with Bernica to the North, down to the Tees, and Deria to the South, as far as Hull. Hutton Lowcross and Guisborough Forest fall in the southern part of Northumbria known as Deria.

AD 793 the Vikings invade Lindisfarne and over 60-70 years continue to invade. By AD 865-870 they continued to invade the country and Alfred the Great, King of the Anglo-Saxons kingdom of Wessex, routed the Viking Invasion. The Vikings subsequently stopped invading.

In 1066 the Norman Conquest defeated the existing Viking and British Tribes and this became the start of the Medieval period. In 1086 a census of Britain was created in the form of the Domesday Book.

Domesday Book, 1086

Following the Norman Conquest of 1066, a census. of sorts , of the lands and towns of the country was prepared in 1086. This is known as the Domesday Book.

A chapter in ‘A History of Cleveland‘, by J Graves, 1806, is available through Google books: Google Play Books. Pages 415 onwards makes reference to Guisborough and Hutton Lowcross as a Parish. It does make reference to the town in the Domesday Book and is associated with Middleton, Tockets, Hoton and (Pinchin)Thorpe. The Domesday Book suggests the area had 10 households, comprising Villagers and one priest. A mill is also mentioned. Guisborough had its own Mill , as did Tockets and Hutton, although the sites of the West Mill at Guisborough and that at Hutton are not known, there is a street called Mill Street that goes down to Chapel Beck. This may have been where a mill was but Chapel Beck, as it currently is, probably does not have sufficient flow to run a mill. The reduction in flow is probably the cause of its demise.

The area came under the hundred of Langbaurgh.

Existing Historic Information

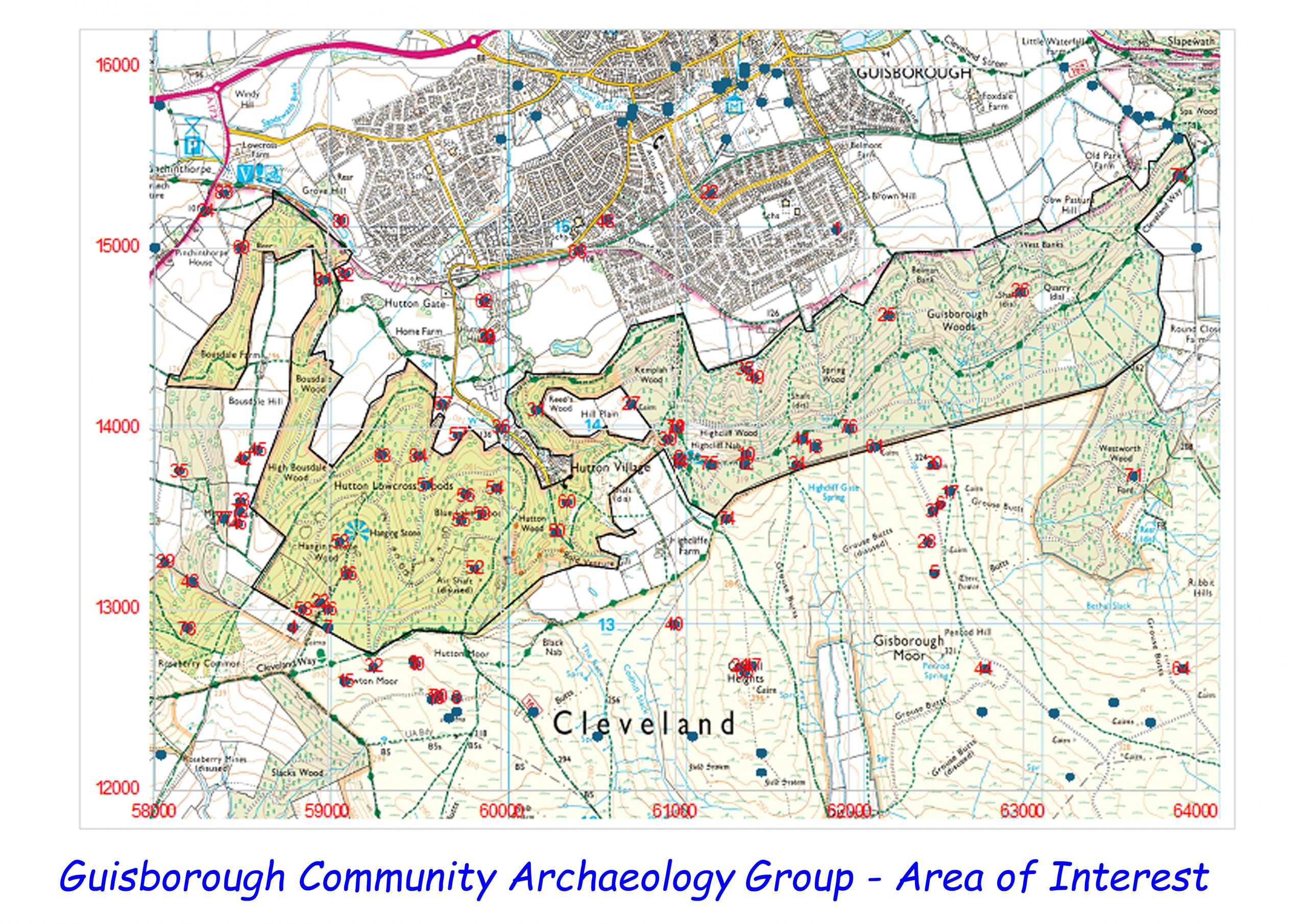

Archaeological research has been done in the past and a list of sites of interest is available through the Historic Gateway, on line. Using this and selecting North Yorkshire and Hutton Village as an area of interest (5km radius) results in 1046 results from 10 of the 16 resources available. These can be listed and the map reference for each can be put in a database and then those falling within a narrower grid of interest can be highlighted. The lists are divided into groups. The HER , or Historic Environment Record, appear here until they are transferred to the relevant local authority Historic Environment Record (HER).

Selecting North York Moors on this site is not that helpful. However by going to the North York Moors Website and searching for NYM HER Map provides all the sites in the North York Moors local authority HER. These can be accessed by clicking on the symbol on the map provided. Sites in the Cleveland HER are indicated on the map, yellow circles, Many of these are still on the main Historic Gateway and the info available from the NYM HER appears to be limited, but useful, nevertheless.

Sites included in the Historic Environment Record for Redcar and Cleveland can be accessed, but only by RCBC staff and is accompanied by a fee!

Plotting those of interest on a map, with a colour coded key for type, period or some other criteria gives a picture of where there is a concentration of activity from the past. A record of those of interest can then be filed. New sites need generating separately, though.

a map of sites has been developed for the Hutton Lowcross area:

Pease Family and Hutton Hall

Wikipedia tells us that:~

The Victorian Gothic house was built in 1866 by Alfred Waterhouse for the Quaker industrialist and member of parliament, Joseph Pease.[1] Pease was involved in local ironstone mining and had bought the estate in 1851.[2] The house and stable block were set in 113 hectares (280 acres) of parkland;[2] laid out by James Pulham the estate included a kitchen garden, an exotic fernery, shrubbery, waterfalls, streams and bridges.[3][4][5]

Hutton Gate railway station was built in about 1867 to serve Hutton Hall, becoming a public station only in 1904.[6][2]

In 1902, a banking crash forced Joseph Pease to sell the house.[3] James Warley Pickering bought it in 1905, and passed to his son.[4] During the 1930s much of the woodland was felled.[4] It was sold again in 1935 to Alfred Pease.[7] During the Spanish Civil War, Ruth Pennyman of Ormesby Hall contacted Alfred Pease to request the use of Hutton Hall to house Spanish nuns and Basque refugees;[3][7] the first 20 children arrived on 1 July 1937.[7] During World War II it was requisitioned by the military.[3] In 1948, the hall, and the 13.5 acres (5.5 ha) which remained of the estate, were sold to John Mathison.[4]

A comprehensive history is provided by The Yorkshire Gardens Trust relating to the original spelling of Hoton Hall and Hoton Green.

Guisborough History Notes: The Pease Family & Hutton is a blog page with a lot of interesting history. There are a number of separate pages relating to Guisborough and the history of the Pease family. The current Hutton Hall was built around 1860, apparently on the site of an existing, older house. Built by Sir Joseph Whitwell Pease 1866/67. JWP was MP for N Durham. Hall built on site (or near) former manor house which was sold by Edward VI in 1550 to Sir Thomas Chaloner. Old hall destroyed. School built 1857. Home Farm—“Hoton Howse”, bought by Chaloner (with Hall) in 1550. Hall: “offices, gardens, hot-houses, hospital for … sanatory treatment of retainers of owner …”. The old hall and adjacent buildings are marked on the 1853 Map, but in slightly different locations than the existing hall and Stable Block (Pease Court). The old hall was demolished and the new Hall placed approximately in the same place and new Stable blocks were also built and the other buildings on the 1853 map were demolished.

Hutton House, on the corner of Hutton Village Road and the Avenue, is of a similar style and architecture. It one time this was used as a hospital.

Alum

Before the 16th Century, Alum mining and sales was controlled by the Catholic Church with the Pope making it illegal to use Alum that wasn’t mined in Italy. With the reformation, woollen dyers in the UK couldn’t get Alum and the means of fixing dyes was through steeping cloth in urine. Hence urine was of value and was sold. As well as importing urine in barrels from big cities, like London, Guisborough collected urine from the local populace. Apparently, the barrels were returned full of Yorkshire Butter!

Burning shale on brush and coal fires, coal from the Newcastle mines, converted the potassium and Aluminium salts into Sulphates. Subsequent steeping of the ash in water and urine resulted in a mixture of Aluminium, Potassium and Ammonium sulphates which was crystallised out. The liquid was evaporated and when sufficient concentration of salts resulted, gauged by a hen’s egg, placed in the brew, floating to the surface, the crystallisation process of further evaporation of water could commence.

Thomas Chaloner, local landowner, realised the possibility of Alum mining in the Guisborough area after noticing the similarity in vegetation between the escarpment at Guisborough and where Alum was mined in Italy. Guisborough was the site of the first Alum mine in the country.

Prior to the Reformation the area was owned by Guisborough Priory having been passed over by Robert de Brus II in 1119 who founded the Augustinian Priory on land and settlements that were ‘pre-conquest’ in the Domesday Book, 1086. The area around Guisborough was a loose collection of settlements including those of Hutton and Thorpe (later to become Pinchinthorpe) mentioned in the Domesday Book. (Ref: Guisborough before 1900 Editors Harrison and Dixon)

Income was primarily at this time from farming, particularly sheepherding and the production of wool. Jet, a semi precious gem stone, has been mined in the area for centuries, and there is evidence of old Jet workings on the escarpment. Shale mining for the production of Alum is also evident and with the railways and the Industrial Revolution of the 19th Century, the opportunity for Ironstone mining.

Jet

Watch this you tube video: Inland Jet Mining in the North York Moors: Chris Twigg (youtube.com) (It is over an hour long, so be aware!)

A shorter description of jet is here: Whitby Jet: A Black Organic Gem, A Rock Similar to Coal (geology.com).

What appears to be a comprehensive discourse on Jet is available online courtesy of the Ebor Jet works Whitby.

I understood that traditionally Jet was dug out of pits. The use of a drift mine, however short, is a development, I believe. Pits were dug in the shale and the shale sorted for pieces of jet, a form of lignite, which can be polished. Jet has been used as jewellery since prehistoric times and is found in bronze age and iron age burial chambers.

I imagine, as the demand for jet rose, and the use of pits was becoming less productive, the Jet Miners started to dig into drifts, making short tunnels. Eventually, jet mines were developed, some of which are extensive, apparently, and extend for several km beneath the surface.

Looking at the 1853 Map of the area, Below the Hanging Stone on Rystone Nab at approximate 775 ft contour, jet pits are marked. These are again marked on the 1893 Map and a quarry is also marked above the Hanging Stone is a quarry (950 ft contour). The map shows signs of ‘craters’. These may be sink holes resulting from collapsed mines? The 1853 Map marks the line of pits as ‘Possible site of British Settlement’. This comes from the thoughts of Walker (1846) but are now believed to be pits. The NT HBSMR identifies a series of pits on the 200m contour around Roseberry Topping. These extend into Guisborough Forest and around the hills just below the Hanging Stone. It was thought these were the remains of Bronze Age (?) round houses and hence the site of a possible British settlement. This is not believed to be the case, despite, in 1926, a JJ Bolton excavated many pits around Roseberry Topping and conclude they were not Jet.

Great Ayton Community Archaeology, in 2006, considered the pits around Roseberry to be jet pits with lines of pits at the 200m, 235m to 245m and 245m contour. Red Ochre from trial borings was identified at the 245m level, which would have made the hill an important location. Ironstone workings were at the lower level and jet workings on the side facing North.

thank you for thank Martin, I very interesting subject